The urban environment facilitates respiratory virus transmission. COVID-19 is now the major threat but the common cold has long had a serious impact on wellbeing,...

The 200 common cold viruses are more prevalent in the British winter. That's mainly because indoor relative humidity drops below the comfort threshold of 40%, making it easier for them to infect. Being infected with one makes us more vulnerable to others, enhancing the misery of the winter 'flu season'.

This article is part of a series on viruses in the built environment, which is a companion to the article on the suite of applications that Atamate is developing to mitigate their effects.

Viruses indoors 1: the urban incubator

Viruses indoors 2: Licht und Luft

Viruses indoors 3: Introducing the common cold

Viruses indoors 5: The winter vomiting bug

The diversity of the common cold

The diversity of the common coldIt's often asked why, if we have vaccines that are very effective against viruses like measles and polio, we have no vaccine against the common cold.

The answer is that there is not one common cold virus but around 200, drawn from several different virus families with different characteristics. The only one we have a vaccine against is influenza, which has been prioritised because the influenza viruses are more likely to cause severe disease than the other cold viruses.

Even influenza is a moving target. At any given time, there are three or four variants somewhere in the world but they're constantly evolving so they can infect someone who is immune to an earlier variant of them. That's why there is a new influenza vaccine issued every year and also why the  influenza vaccine is not as effective as vaccines against more static targets like polio and measles. It does reduce the chances of becoming ill with influenza but the 'flu jab' can't completely protect us.

influenza vaccine is not as effective as vaccines against more static targets like polio and measles. It does reduce the chances of becoming ill with influenza but the 'flu jab' can't completely protect us.

The influenza viruses only account for 5-15% of colds. The commonest common cold viruses are the hundred varieties of rhinovirus, which account for 30-50%. There's no prospect of a vaccine that can cover all of them, let alone the other hundred cold viruses of various virus families.

COVID-19 is caused by a member of the coronavirus family, which is different again. It's related to the four 'endemic' coronaviruses that cause 10-15% of colds and have a nasty habit of interfering with the immune response. The immune system can eliminate them as efficiently as any other cold virus but it forgets them after a few years so they all infect us repeatedly through our lives. It remains to be seen whether COVID-19 has the same trick but we cannot assume that someone who has had COVID-19 has any long-term immunity to it.

For those of us living in the UK, or indeed anywhere in the temperate zone of the northern hemisphere, colds are indelibly associated with the winter. We're so used to dire reports of hospitals filling up over the winter that we sometimes call it the 'flu season', which is slightly misleading as the influenza viruses account for one or two of several types of cold viruses circulating most winters.

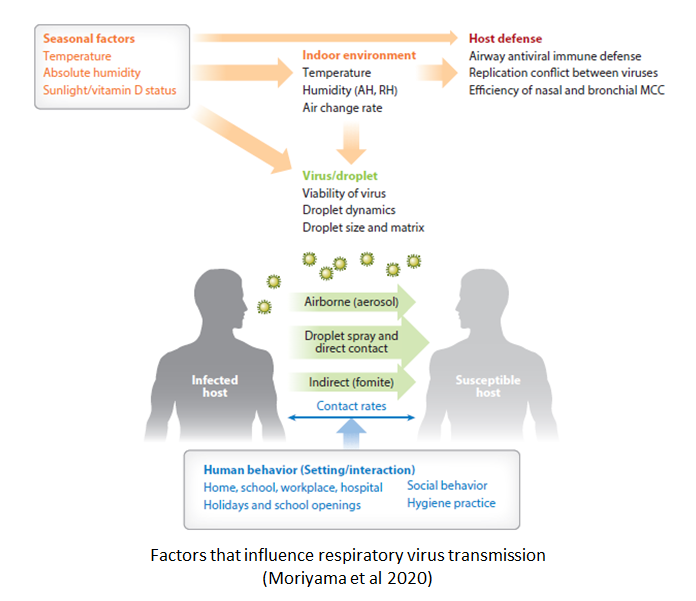

While it's often stated that the seasonality of respiratory viruses is due to the colder weather, it's less often stated that the reason is not directly due to the air temperature but an indirect effect of air  temperature on relative humidity. In fact, cold viruses circulate throughout the year in the tropics where year-round air temperatures are often equivalent to a heatwave in Britain.

temperature on relative humidity. In fact, cold viruses circulate throughout the year in the tropics where year-round air temperatures are often equivalent to a heatwave in Britain.

The major reason why colds are seasonal is that we're more vulnerable to infection at low relative humidity. During the winter, heating air as it moves indoors drops the relative humidity which is one way in which the indoor environment actively helps cold viruses to infect us.

Relative humidity is a measure of how much moisture is in the air compared to how much it can carry. The warmer the air, the more moisture the air can carry so raising the air temperature without changing the amount of moisture in it will drop the relative humidity.

The rate at which liquid water evaporates is dependent on the relative humidity. Low relative humidity means that the air can carry more moisture than is in it, leading to rapid evaporation.

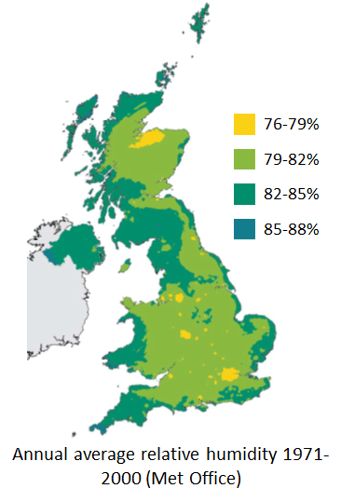

In the UK, the outdoor relative humidity is usually over 70% [PDF], which is above the 40-60% humidity recommended in the TM40 memorandum on health and wellbeing recently published by the Chartered Institute for Building Service Engineers (CIBSE). For most of the year, the indoor air temperature is higher than the outdoor temperature so heating it as it moves indoors drops the relative humidity.

The greater the difference between the outdoor and indoor air temperatures, the lower the indoor relative humidity. During the winter, the difference between indoor and outdoor temperature is so high that the indoor relative humidity is usually below the 40% comfort threshold.

The greater the difference between the outdoor and indoor air temperatures, the lower the indoor relative humidity. During the winter, the difference between indoor and outdoor temperature is so high that the indoor relative humidity is usually below the 40% comfort threshold.

In large commercial buildings which need air conditioning for most of the year, the problem of low humidity is not restricted to the winter. The air conditioning process involves cooling air to below the comfortable temperature, causing moisture to condense out of it, and then passing it into rooms where it is slightly warmer where the higher carrying capacity equates to low relative humidity.

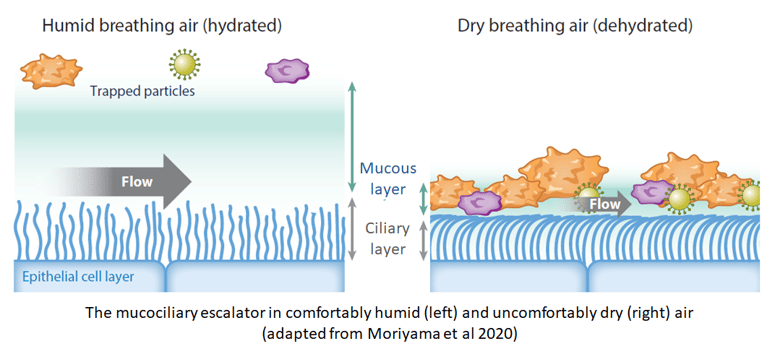

At such low relative humidity, moisture in the room evaporates quickly and unfortunately for us, one source of that moisture is one of our major defences against cold viruses: the charmingly named mucociliary escalator. The 'muco' refers to the layer of mucus coating our respiratory tract, which traps viruses before they can latch on to the cells they need to infect. The 'ciliary' refers to the minute tendrils called cilia which waft the mucus upward and out through the nose and mouth, carrying trapped viruses with it.

Mucus is thickened into the gunge we're familiar with by a protein matrix but by volume, it's mostly water. When the relative humidity drops below 40%, the water evaporates, drying out the protein matrix and leaving the mucus thinner and more solid. Ultimately it becomes so solid that the cilia can no longer move it. As the mucociliary escalator breaks down, it no longer moves trapped viruses out of the respiratory tract but holds them close to the cells they need to infect.

We're all familiar with the consequences: every winter, we face a workplace full of coughs and sneezes leave us waiting for the inevitable tickle in the throat that tells us we’re next.

The failure of the mucociliary escalator makes us vulnerable to all of the 200 cold viruses and when we catch one, we're likely to be infectious to other people for several days before we know we've got it. That means that the low relative humidity of the indoor environment not only makes us vulnerable but surrounds us with people likely to be breathing out cold viruses. In short, it causes the flu season.

The failure of the mucociliary escalator makes us vulnerable to all of the 200 cold viruses and when we catch one, we're likely to be infectious to other people for several days before we know we've got it. That means that the low relative humidity of the indoor environment not only makes us vulnerable but surrounds us with people likely to be breathing out cold viruses. In short, it causes the flu season.

When we're infected by one virus, the immune system focuses its resources on it to the extent that it has less to spare to respond to any other infections that come along. Even when it's cleared a cold virus, it takes two or three weeks to return to its normal state of general readiness for the next one.

That's why a cold virus can open the door to pneumonia caused by a bacterial infection. It also means that if we get infected by a second cold virus before our immune system has fully returned to its normal state, that second cold is likely to hit us much harder than it would have done if we hadn't had the first. Because cold viruses tend to come thick and fast in the winter 'flu season' rather than being evenly spread across the year, those nasty follow-up colds tend to happen a lot.

That's why a cold virus can open the door to pneumonia caused by a bacterial infection. It also means that if we get infected by a second cold virus before our immune system has fully returned to its normal state, that second cold is likely to hit us much harder than it would have done if we hadn't had the first. Because cold viruses tend to come thick and fast in the winter 'flu season' rather than being evenly spread across the year, those nasty follow-up colds tend to happen a lot.

At the time of writing, COVID-19 has shown no signs of following a seasonal pattern. It's more infectious than most of the cold viruses and as it continues to spread through the USA, it's evidently capable of spreading during the temperate summer. However, it infects in the same way as a cold virus so we can expect it to become even more infectious in a population of people with dry mucociliary escalators and more deadly if they are run down by other cold viruses. COVID-19 is bad in the summer but likely to be worse in the winter.

If you’d like to know more about how Atamate Building Intelligence can support the wellbeing of the people who live and work in the urban environment, ask us on the form and we'll be happy to discuss it.

The urban environment facilitates respiratory virus transmission. COVID-19 is now the major threat but the common cold has long had a serious impact on wellbeing,...

The modern urban environment is ideal for the transmission of respiratory viruses, which is why the common cold spreads so fast. COVID-19 spreads using the same...